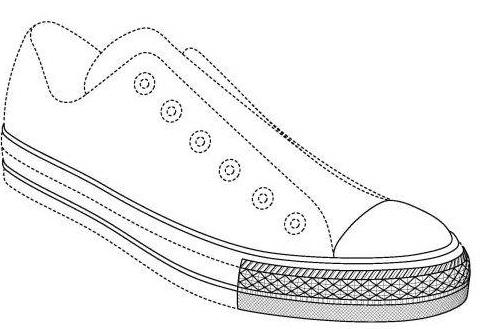

On October 30, 2018, a divided Federal Circuit issued a decision in Converse, Inc. v. ITC, whereby it created a new test for secondary meaning and placed limits on trade dress infringement. The Federal Circuit found registered trade dress carries a presumption of secondary meaning only prospectively from the date of registration. Prior to the date of registration, the mark owner must show that the mark acquired secondary meaning prior to the first infringing use for each accused infringer. Further, the Federal Circuit held that product design trade dress can only infringe if it is “substantially similar” to the protected trade dress. The ITC found that the midsole portion of the below Converse All Star shoes was not a protected trademark, invalidating the Chuck Taylor trade dress of U.S. Trademark Registration No. 4,398,753 and rejecting the existence of common-law rights in the mark and, therefore, Converse could not prove a violation of section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930.1 On appeal, the Federal Circuit vacated and remanded for further consideration.

Slip. op. at 4

The ITC Proceedings

On October 14, 2014, Converse filed a complaint with the ITC alleging violations of section 337 by a number of respondent companies.2 In its complaint, Converse accused the intervenors of infringing Converse’s trade dress rights arising from its ‘753 registration, which issued on September 10, 2013, and describes design elements on the midsole of certain Converse shoes. The ‘753 registration describes the mark as consisting of “the design of the two stripes on the midsole of the shoe, the design of the toe cap, the design of the multi-layered toe bumper featuring diamonds and line patterns, and the relative position of these elements to each other. The broken lines show the position of the mark and are not claimed as part of the mark.” The mark is depicted in the above drawing from the ‘753 registration.

Converse also asserted infringement of its common law trade dress rights in the trade dress described in the ‘753 registration.

The ITC instituted an investigation on November 17, 2014. During the investigation, Converse asserted that it used the mark since 1932, and the mark had acquired secondary meaning. The intervenors countered that the mark did not acquire secondary meaning, arguing that Converse’s use of the mark was not substantially exclusive and that survey evidence showed that consumers did not associate the mark with a single source.

On November 17, 2015, relying on the presumption of secondary meaning afforded a registered mark, the Administrative Law Judge issued an initial determination finding the ‘753 trademark not invalid and infringed by the intervenors. Treating the common-law mark and registered mark as two separate trademarks, the ALJ also found that Converse did not establish secondary meaning for the common-law mark.3

On June 23, 2016, the ITC issued its final determination, reversing the ALJ’s determination that the registered mark was not invalid.4 Like the ALJ, the ITC treated the registered mark and the common-law mark as two separate marks. The ITC affirmed the ALJ’s finding that the common-law mark had not acquired secondary meaning. Finally, the ITC found that if either mark was not invalid, it was infringed by the accused intervenor products.

The Federal Circuit’s Decision

Finding that “the ITC made a series of errors,” the Federal Circuit vacated the ITC’s final determination and remanded for further consideration in view of the court’s opinion.

The Timing of the Secondary Meaning Inquiry

According to the Federal Circuit, the ITC’s first error was failing to distinguish between the intervenors that began infringing before Converse obtained its ‘753 registration and those that began infringing after Converse obtained its ‘753 registration, as “it is confusing and inaccurate to refer to two separate marks — a registered mark and a common-law mark. Rather, there is a single mark, as to which different rights attach from the common law and from federal registration.” Slip op. at 7.

To establish trademark infringement under the Lanham Act, a plaintiff, here Converse, must prove: “(1) it has a valid and legally protectable mark; (2) it owns the mark; and (3) the defendant’s use of the mark to identify goods or services causes a likelihood of confusion.”5 To be valid and protectable, trademarks must be distinctive of a product’s source.

There are two ways to establish distinctiveness — a mark can be inherently distinctive (i.e., its intrinsic nature serves to identify a particular source) or a mark can acquire distinctiveness (i.e., the mark can acquire secondary meaning, “which occurs when in the minds of the public, the primary significance of the [mark] is to identify the source of the product rather than the product itself.”6

Because Converse sought protection for unregistered product-design trade dress, and the Supreme Court in Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., Inc.7 held that product-design trade dress (unlike word marks and product-packaging trade dress) cannot be inherently distinctive, Converse was required to show that its mark acquired secondary meaning — i.e., that the relevant consumers associate the particular product features with a particular source of goods.

According to the Federal Circuit, the ITC erred in not determining the relevant date for assessing the existence of secondary meaning “[b]ecause the relevant date is so important to the secondary-meaning analysis, we find that a specific determination of secondary meaning as of the relevant date must be made.” Slip op. at 9.

While the Lanham Act affords the owner of a registered mark the presumption of validity, that presumption does not apply prior to registration. Accordingly, for the intervenors whose first uses predated the ‘753 registration’s September 10, 2013, registration date, Converse was required to establish, without the benefit of any presumption, that its mark acquired secondary meaning prior to that intervenor’s first use.8

In Converse, the court modified this “first infringing use” language to set a rough five-year cutoff as it applied Section 2(f) of the Lanham Act. Determining that the ITC “relied too heavily on prior uses long predating the first infringing uses and the date of registration,” the Federal Circuit explained that “[t]he secondary meaning analysis primarily seeks to determine what is in the minds of consumers as of the relevant date,[9] and factor 2 [i.e., length, degree, and exclusivity of use] must be applied with this purpose in view.” Slip op. 17. Accordingly, it is the trademark owner’s and third parties’ use “in the recent period before” the first infringing use and/or the date of registration that is important. Id. And looking to section 2(f) of the Lanham Act10 for guidance as to what “in the recent period before” means, the Federal Circuit found that:

[w]hile section 2(f) cannot be read as limiting the inquiry to five years before the relevant date, it can and should be read as suggesting that this period is the most relevant. As a result, in evaluating factor 2, the ITC should rely principally on uses within the last five years. The critical issue for this factor is whether prior uses impacted the perception of the consuming public as of the relevant date.

Slip op. at 19.

Thus, the court found that five years of exclusive and continuous use can create a presumption of secondary meaning.

The Standard for Determining Whether a Mark has Acquired Secondary Meaning

In addition to the presumption and timing issues, the Federal Circuit also found that the ITC erred in its analysis of secondary meaning. Noting that “[e]ach circuit that has addressed secondary meaning — 11 circuits in all — has formulated some version of a multifactor test [to assess whether a mark has acquired secondary meaning] similar to the test adopted by the ITC” (slip op. at 15), the Federal Circuit “clarif[ied]” its own test, identifying the following factors that should be “weighed together”:

-

association of the trade dress with a particular source by actual purchasers (typically measured by customer surveys);

-

length, degree, and exclusivity of use;

-

amount and manner of advertising;

-

amount of sales and number of customers;

-

intentional copying; and

-

unsolicited media coverage of the product embodying the mark.

Slip op. 16-17.

The Federal Circuit found error in the ITC’s overly inclusive use of Converse and third-party marks in its secondary-meaning analysis, explaining that “[a]lthough we agree with the ITC that evidence of the use of similar but not identical trade dress may inform the secondary-meaning analysis, we think such uses must be substantially similar to the asserted mark.” Slip op. at 20 (emphasis added). Of particular note, “substantially similar” is a standard used in copyright cases, not in trademark cases.

And with respect to the use of survey evidence to show that Converse’s mark had not acquired secondary meaning, the Federal Circuit criticized the ITC for giving substantial weight to a survey conducted two years after Converse’s registration of the mark. The Federal Circuit noted that while such evidence may be relevant to secondary meaning of the registration (as it is within the five-year period of registration), it says little — if anything — about whether Converse’s mark acquired secondary meaning as of the intervenors’ first infringement (which predated the registration in most cases by about five to 10 years). Accordingly, the Federal Circuit observed that “with respect to Converse’s claims of infringement against the intervenors, the ITC should give the [survey evidence] little probative weight in its analysis, except to the extent that the [survey evidence] was within five years of the first infringement by one of the intervenors.” Slip op. at 22. Of note, this calls into question the relevancy of conducting survey evidence when trying to establish secondary meaning of common law rights that significantly predate a registration.

Standards for Determining Likelihood of Confusion

The Federal Circuit explained that “[t]he likelihood-of-confusion analysis for determining infringement turns on the similarity of the accused products to the asserted mark” (slip op. at 24), and then noted the ITC’s inconsistency in applying that test. In that regard, the ITC found no infringement by an accused product missing one of the ‘753 registration elements (two stripes on the midsole), yet found infringement by accused products missing a different element of the ‘753 registration (the multi-layered toe bumper featuring diamonds and line patterns). Because only accused products that are substantially similar to the asserted design can infringe, the Federal Circuit directed the ITC to reassess its infringement findings. As noted, above, substantially similar is a standard used in copyright cases, not in trademark cases.

Conclusion

Whether a trademark owner’s mark has acquired secondary meaning is an important question litigated in many cases involving trademark validity. The Federal Circuit’s Converse opinion created a new test for secondary meaning and placed limits on trade dress infringement. The Federal Circuit opinion found registered trade dress carries a presumption of secondary meaning only prospectively from the date of registration. Prior to the date of registration, the mark owner must show acquired secondary meaning prior to the first infringing use for each accused infringer. The Federal Circuit articulated a limitation on product trade dress infringement, claiming product design trade dress can only infringe if it is substantially similar to the protected trade dress, which arguably deviates from the likelihood of confusion standard set forth by other courts.