Business news programs, real-time financial market coverage, and newspaper articles are replete with stories of tenants shuttering stores and being unable to pay rent under their leases. Commercial businesses not deemed “essential” have shuttered also and, while many attempt to continue their businesses from home, the revenue stream for certain businesses will slow precipitously. Some of these tenants will go out of business and the collection of the past-due rent and other charges will be left to a bankruptcy proceeding or other workout. Other tenants, however, will reopen and it will be the job of landlords and tenants to deal with the past-due rent and other defaults under the lease. It is likely that some tenants may view the near future economic landscape as perilous and, in connection with curing prior defaults, request a restructuring of the post-default payments under the lease or, in some cases, a reduction in, and/or deferral of, the rent and other charges under the lease. Responding to the request for a lease restructuring involves more than the business and credit worthiness issues presented by a modification. Tax issues often arise in connection with lease modifications and present unexpected tax consequences for both landlords and tenants. Landlords and tenants need to understand the tax pressure points for both sides in a lease restructuring in order to better develop a plan for modifying the lease that meets the parties’ business and tax goals.

In an earlier paper, we outlined the income tax consequences of defaults and restructurings under loan agreements for both borrowers and lenders. This paper summarizes the income tax considerations for landlords and tenants from defaults under leases and restructurings of leases to accommodate the fallout from the current economic upheaval. It does not address leasing arrangements that fall under the “anti-tax avoidance” provisions of Section 467. It is no substitute for tax and legal advice addressed to your specific circumstances. In general, the recent fiscal stimulus legislation did not change the basic rules summarized below.

Further, this paper does not discuss the possibility that a restructured lease could be reclassified by the IRS into a joint venture with the landlord. Modifications to the lease in which the landlord assumes more of the risk of loss for the business operations of the tenant or participates in the net income, or appreciation in value of the property, of the tenant run the risk of converting the lease into an agreement more properly characterized as a partnership for income tax purposes.

Overview

Generally, there are no federal income tax consequences from a default or restructuring under a lease unless the changes to the legal rights, obligations, or payments under the lease constitute a “substantial modification.” If there is a substantial modification of the lease, the lease, as modified, is treated as a new lease, effective on the date of the modification, and the new lease must then be evaluated under Section 467 of the Code to determine whether, and to what extent, the lease is classified as a Section 467 rental agreement. If the lease is classified as a Section 467 rental agreement, the landlord and tenant are required to recognize rent on an accrual basis with an imputed interest factor if rent payments are significantly deferred or prepaid. In the case of certain “tax avoidance” transactions, the landlord and tenant are required to recognize the rental and expense income ratably over the lease term without regard to the rent allocations in the lease itself.

The rules of Section 467 are complex. It is not always obvious whether the terms of a modified lease cause it to become a Section 467 rental agreement to which those rules apply. The Section 467 rules can require an application of time value-of-money principles, and often lead to some surprising results for both landlords and tenants. The Section 467 rules require that the modified lease be analyzed by bifurcating the lease into pre- and post-modification period items. Pre-modification period items are limited to those items attributable to periods before the modification that are unaffected by the modification. These items are reported by landlord and tenant without regard to the modification. Post-modification period items are treated as attributable to a separate lease entered into on the effective date of the modification.

There are safe harbors in the regulations that permit some alterations in the terms of a lease without triggering a substantial modification and these may be important for both the landlord and tenant in the current environment. For example, a contribution by the landlord to the tenant in the form of a waiver of the tenant’s obligation to pay common area maintenance charges or to reimburse the landlord for the tenant’s shares of property taxes generally would not result in a substantial modification of the lease.

The reason why it is important to understand how these rules work is that the post-modification period items are treated as if they are part of a separate agreement with a term equal to the remaining term on the date of modification. Suppose that a landlord agrees to modify the payment terms for the lease of a tenant in financial distress? The modified lease could fall under the rules of Section 467 of the Code. If the landlord agreed to waive or defer the payment of some portion of the rent, the post-modification rent payment allocations might make the rental payments subject to the rules for increasing or deferred rent under Section 467. Falling under these rules could change how the landlord and the tenant are required to account for rent under the modified lease.

Unless subject to Section 467, landlords and tenants account for items of rental income and deduction under their usual method of accounting, i.e., under the “all events test” if an accrual method taxpayer, and under the “actual or constructive receipts” test if a cash method taxpayer. The Section 467 rules are far more complex, however. If they apply to rents under a lease, the landlord and tenant could be required to account for the rent under the lease using present value principles rather than in accordance with their regular accounting methods for rent payments.

The following example illustrates one of the pitfalls of falling into the Section 467 rabbit hole.

Example One H LLC owns a suburban professional office building with multiple tenants. One tenant, P LLP, is a relatively new law firm that went into occupancy one year ago under a 10-year lease at market rates with market-level passthroughs. The lease requires an annual rental payment of $300,000 ($25,000/month) and that amount is identified in the lease as the fixed annual and monthly rental. H required that P post a letter of credit to secure its payments under the lease in the amount of $500,000.

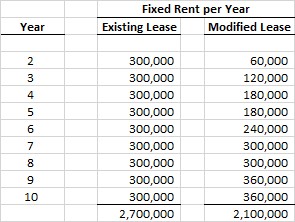

As a result of the economic turmoil resulting from COVID-19, P is struggling financially and is in monetary default under the lease, beginning with the first month of year two of the lease. H is prepared to work with P to keep P in the building, and paying its shares of the lease passthroughs. H suggested that it would waive the fixed rent (but not the passthroughs) for the six-month period beginning with the date of the default (that is, for the first six months of year two). In addition, H would call the letter of credit to the full extent of the $500,000 and would treat the $500,000 as prepaid rent for the rental period beginning with the seventh month of year two. (H would have the right to retain any portion of the remaining prepaid rent in the event P terminates the lease for any reason or no reason.) No additional letter of credit would be required. Finally, the lease would be amended to reduce the annual rent beginning in the seventh month of year two of the current lease and to provide for increasing rents as follows:

Both H and P are anxious to sign up the lease modification and believe that there should be no tax issues.

As discussed below, there are two important tax issues presented by the above proposal: (i) what the parties believe to be prepaid rent includible in the landlord’s income over the approximately 42 months beginning with the seventh month of year two will likely be treated as rent that is includible in the landlord’s income in the year that the landlord draws against the letter of credit; and (ii) because the lease provides for increasing rents, i.e., the annualized fixed rent allocated to a period under the lease exceeds the annualized fixed rent allocated to any other period under the lease, the lease is a Section 467 lease agreement. Therefore, the fixed rent for any period post-modification will be the proportional rental accrual amount.

What Are the Key Characteristics of Section 467 Lease Agreements?

There are relatively clear rules for when a lease is subject to Section 467. Absent a failure to state a schedule of rent payments in the lease, which is unusual in a typical commercial lease, a lease is a “467 rental agreement” if: (i) the lease involves the use of tangible property, (ii) the aggregate rental payments over the term of the lease are more than $250,000, and (iii) one of the three following conditions is met:

-

the payment of some rent under the lease is deferred beyond the close of the calendar year following the calendar year in which the use occurs (deferred rent);

-

the cumulative amount of rent payable as of the close of a calendar year exceeds the cumulative amount of rent allocated as of the close of the succeeding calendar year (prepaid rent), or

-

there are increases or decreases in rent during the term (stepped rents);

A lease can also be a 467 rental agreement if the lease is a tax avoidance sale-leaseback or a long-term lease. Those leases can be subject to the so-called rent-leveling provisions of Section 467. Finally, a lease that has increasing or decreasing payments, and leases with deferred or prepaid rent, may be required to impute interest on the deferred or prepaid amount, accounting for the payments under the lease using the proportional rental accrual method.

A key concept under the Section 467 rules is whether rent is “allocated” to a period. Rent is allocated to a period if the rental agreement unambiguously specifies, for periods no longer than a year, a fixed amount of rent for which the tenant becomes liable on account of the use of the property during that period, and the total amount of fixed rent specified is equal to the total amount of fixed rent payable under the lease. If the rental agreement is silent regarding the allocation of rent to a period, the amount of fixed rent allocated to a rental period is the amount of fixed rent payable during that rental period. The allocation under the rental agreement must be meaningful so that a provision in a lease by which the tenant forfeits the amount of prepaid rent on account of any termination of the lease, e.g., the amount of prepaid rent is reduced to $0, is interpreted by the IRS as meaning that there is no allocation of that amount as rent under the lease and any prepaid rent is includible by the landlord in income, and deductible by the tenant, in the year paid. Thus, in order for landlords and tenants to establish that a payment is a pre-payment of rent, the tenant (or tenant’s creditors or bankruptcy estate) should have the right to recover the unearned prepaid rent in the event of a lease termination, including a disavowal of the lease in the case of the tenant’s bankruptcy. Of course, that condition makes the use of prepaid rental arrangements difficult to structure for other than the strongest credits.

If a lease is a 467 rental agreement, the parties are required to use the accrual method of accounting, irrespective of their regular method of accounting. In measuring the $250,000 rental amount, contingent payments (other than passthroughs like CAM and reimbursements) are taken into account at their expected value.

If the agreement is a 467 rental agreement, rents must be taken into account by the parties under the allocation of rent provided for in the lease, rather than in accordance with the taxpayer’s method of accounting. Where there is no allocation of rent in the lease, the rent is taken into account in accordance with the schedule for rental payment. A cash method tenant can gain an advantage by treating the lease as a 467 rental agreement because the accrued but unpaid rent is available as a current deduction. A cash method landlord, on the other hand, would be required to include the scheduled rent in income even though the rental payment was deferred. The typical commercial lease provides a payment schedule and the rental income and deductions must be taken into account in accordance with that schedule.

The important takeaway here is that, if the lease is not a 467 rental agreement at its inception, the parties should try to avoid entering into a restructuring that causes the modified lease to be treated as a 467 rental agreement, particularly if the landlord is a cash method taxpayer who would then be required to account for the rental income using the accrual method of accounting. For larger properties, that is not likely to be a consideration because most landlords of larger properties would already be accrual method taxpayers.

What Is a Substantial Modification of a Lease for Income Tax Purposes?

A “modification” of a lease agreement is any alteration, including any deletion or addition, in whole or in part, of a legal right or obligation of the landlord or tenant, regardless of whether the alteration is evidenced by an express agreement (oral or written). A modification is substantial if it is economically substantial.

Fortunately, the IRS Regulations contain several safe harbors so that relatively common lease modifications typically are excluded from the definition of a substantial modification.

The most common modifications under the safe harbor are those relating to changes in the rental payments based on changes in the underlying financing. This is a common type of modification in leveraged lease transactions and unlikely to be implicated by a financial restructuring resulting from an event of default or in anticipation of a default.

There is a “no-modification” safe harbor for a change in the amount of fixed rent allocated to a rental period that, when combined with all previous changes in the amount of fixed rent allocated to the rental period, does not exceed 1 percent of the fixed rent allocated to that rental period prior to the modification.

Finally, there is a safe harbor for a change to provisions in the lease requiring that the tenant reimburse the landlord for third-party costs, e.g., property taxes, insurance, or maintenance, for late payment charges, and for certain other contingent payments under the lease.

In determining whether there has been a substantial modification of a lease, all of the agreements of the parties are taken into account. Therefore, any agreement, e.g., side-letter, which involves the rights and obligations of the landlord or tenant relating to post-modification period items, must be taken into account in determining if the modification is substantial and how the lease must be treated post-modification.

Why Do Landlords and Tenants Care If a Lease Is Substantially Modified?

Landlords and tenants care if a lease is substantially modified if either the pre-modification lease (old lease) or the modified lease (new lease) was or will be subject to the provisions of Section 467.

Old lease not a 467 rental agreement, but new lease is a 467 rental agreement.

Example Two X LLC, an accrual method taxpayer, entered into a ground lease to G Corp., a fitness club. X constructed a free-standing building on the site on behalf of G. In lieu of paying X a construction management fee for completing the building, X and G agreed that G would make a rent prepayment ($4,500,000) approximating the amount of the fee and that the prepayment would be made when construction was substantially completed. Although X’s use of the money was not restricted, G (or G’s creditors) had the right to the return of the portion of the prepayment allocated to periods not used in the event of a termination of the lease other than for cause. The lease had a rental schedule showing that the prepayment would be allocated ratably over the term of the lease, i.e., $300,000/year. The rent under the lease was required to be accounted for using the proportional rental accrual rules, meaning that X was deemed to pay interest to G on account of the prepayment.

The lease had a term of 15 years and required, in addition to the prepaid rent, fixed payments of annual rent of $75,000 per year, contingent rent based on a fixed percentage of G’s sales above a floor, plus CAM and a reimbursement for property taxes. The fixed annual rent was adjusted based on the changes in a recognized financial index on each five-year anniversary. The lease was not a 467 rental agreement, notwithstanding that it was a long-term lease.

As a result of economic conditions, G was required to close its facility temporarily, could not make the required payments under the lease, and the lease went into monetary default. At the time of the default, the lease had 12 years remaining on its term. Rather than recover the property, X decided to work with G to modify the terms of the lease, effective as of the date of the initial payment default. The terms of the workout provided that term of the lease was extended to 15 years following effective date of the modification. No portion of the prepaid rents were returned, but the remaining prepaid rents were allocated ratably over the new term of the modified lease ($240,000/year). The new lease maintained the fixed rent payment of $75,000, plus the CAM and other reimbursements, but eliminated the rent indexing. It deferred all payments otherwise due during the 24-month period beginning on the effective date of the modification. These amounts became payable, in full, at the termination of the lease, without interest. Finally, the balance of the prepaid rent became due upon the termination of the new lease, for any reason, including the insolvency of the tenant or the failure to keep the premises open for business for any six consecutive day period, regardless of cause, i.e., no out for force majeure.

The modification is a significant modification of the old lease. As a result, the new lease must be tested under the Section 467 rules. On its face, the new lease has both prepaid rent and deferred rent so that it is subject to the Section 467 rules. Without taking into account the new provision for the forfeiture of the prepaid rent, the landlord and the tenant would have to account for the rental income and deduction under the new lease using the proportional rental accrual method, which recharacterizes a portion of the payments under the lease to provide for interest on the prepayment and the deferred payments, where there is no interest provided for or the rate of interest is inadequate under these rules. Where there is no interest on the deferred payments, as in example two, the landlord and tenant must recognize the proportional rent rather than the stated or allocated rent under the new lease.

Applying the proportional rent accrual rules requires that the landlord and tenant perform present value calculations involving the present value of the amount of rent allocated to the period and the present value of all payments due under the New Lease. The calculation requires that the amount of rent allocated to a period be bifurcated into “rent” and “interest” by reference to a fraction, the numerator equaling the present value of the allocated rent payment for the period and the denominator being the present value of all payments under the lease. The difference between the proportional rent accrual and the aggregate rent payment allocated to the period is reported as interest income or interest expense.

Reclassifying the income and expense of the landlord and tenant under the new lease could have important tax consequences to one or both of the parties. For example, by creating deferred rent without adequate stated interest, the tenant could be forced to recognize significant interest expense in the early years of the new lease that could be disallowed under Section 163(j).

There is another, more insidious tax issue presented by the restructuring, however. The old lease had prepaid rent and, under the Section 467 rules, the parties had to account for the imputed interest on the amount of the prepayment. By lengthening the term over which the remaining balance of the prepayment was allocated, the landlord and tenant would have reduced the present value of the imputed loan amount and would have triggered ordinary income to the tenant equal to the amount of the reduction in the 467 loan balance. This would have given rise to a loss to the landlord and both the income and loss would be recognized in the taxable year of the modification. As bad as that might seem, there is another tax issue lurking in the problem that poses a far worse problem for the landlord. By permitting the landlord to seize the balance of the prepaid rent on account of any termination of the new lease, the IRS could challenge the allocation as rental income and deduction of the balance of the prepayment over the remaining term of the lease. Instead, the IRS could be expected to assert that the full amount of the balance of the prepaid rent was includible taxable income of the landlord on the effective date of the modification because the landlord’s right to the prepayment was not subject to use and occupancy of the premises by the tenant.

Example two illustrates a case where the landlord and tenant would be incentivized to avoid a significant modification of the old lease. In addition to the change in the annual rental income and interest income amounts, triggering a significant modification also involves the added compliance costs to calculate and apply the Section 467 rental rules.

Example Three Taxpayer M, an LLC classified as a partnership for income tax purposes, enters into a 20-year ground lease with tenant W, with the annual rent being allocated $1.5 million per year. W agrees to pay M $18 million on the date the premises are accepted and the lease commences. The lease agreement allocates the $18 million as a payment of the first year’s rent and a prepayment of rent for the next 11 years. M would be required to refund the balance of the prepayment in the event of the termination of the lease other than for cause.

At the beginning of the third lease year, M and W agree to a restructuring of the lease because of changed economic circumstances. The rent for years three – 20 is reduced to $1.2 million annually and the rent for year three is waived entirely. No portion of the rent prepayment ($15,000,000 following the subtraction of the two years rent) is refunded. The new lease applies the prepaid rent to the rent due beginning with year four and ending 12.5 years after the commencement of the lease year four. Previously, the prepaid rent would have been exhausted at the end of year 12. Under the New Lease, the prepaid rent is allocated through mid-year of year 16.

The lease was significantly modified. Before the modification, the lease agreement was a Section 467 agreement because it provided for prepaid rent without stated interest. Rent under the lease for the pre-modification period was taken into account under the proportional rent accrual method. The landlord was deemed to pay interest to the tenant and the tenant was deemed to pay additional rent equal to the deemed interest. Post-modification, the agreement still provides for prepaid rent without interest, but the amount of the so-called 467 loan deemed to be created between the landlord and tenant at the time of the prepayment has changed. The amount of the 467 loan has been reduced as a result of the modification because the last rental payment to which it will be applied is now later than pre-modification and the 467 loan balance is based on present values.

Because the balance in the Section 467 loan was decreased as a result of the modification, the difference is taken into account, in the taxable year in which the modification occurs, as a reduction of the rent previously taken into account by the landlord and tenant. Therefore, the landlord would recognize a taxable loss in the taxable year of the modification and the tenant would recognize taxable income. The collateral tax consequence from the change in the amount and timing of the payments is likely one that is unexpected by the parties.

IRS Remedies for Taxpayers That Ignore the Change in Classification of a Lease Resulting From a Substantial Modification

The Section 467 Regulations simply assume that the parties to a lease modification that is a significant modification for Section 467 purposes will change their reporting for the income and expenses under the new lease. If the classification of the lease as a Section 467 rental agreement changes as a result of a substantial modification and one or both of the landlord and tenant fail to change their accounting for the lease, the IRS likely would assert that the taxpayer adopted an improper method of accounting for the lease income or expense. When identified on examination, the IRS would normally make the change in the earliest year under audit and require the taxpayer to take the Section 481(a) adjustment, computed as of the beginning of the year of change, into account entirely in the year of change.

In the case of a partnership, this possibility puts special emphasis on how the partnership or LLC agreement accounts for “imputed underpayments” under the new centralized partnership audit rules (CPAR). Before CPAR, the audit adjustment would have been determined at the partnership level and flowed through to the returns of the partners for the taxable years in which the adjustments to partnership income and loss were applicable. Post-CPAR, the partnership, in the first instance, is responsible for the tax on the amount of the adjustment in the year under review. As a result, that tax burden naturally falls on the members in the year in which the IRS makes the adjustment and determines the amount of the imputed underpayment. Partners or LLC members who benefited from the understatement of income or overstatement of expense in the early period may no longer be partners or members and the partnership’s or LLC’s ability to recover payments from the no-longer partners or members will be solely a function of the language in the company’s agreement. There is no federal rule of contribution and, in many cases, partnerships, LLCs, and withdrawing partners/members enter into broad releases that may further impede the entity’s ability to recover the tax owed from former partners/members. When the parties are considering the types of lease modifications discussed above, it would make sense to review the partnership’s or LLC’s tax controversy language and determine if it contains clawback provisions and, if so, whether those provisions are adequate in view of CPAR.

Conclusion

In addition to the income tax points discussed above, landlords and tenants must also consider the impact of any modification or restructuring of a lease on their financial statements. Before the current economic crisis, the new Financial Accounting Standards Board lease accounting rules (ASC Topic 842) were scheduled to go into effect in 2021 for non-public business entities.

The rules for section 467 lease agreements are complex and contain a number of surprising and unexpected consequences. Most typical commercial lease agreements do not involve Section 467 issues because they generally do not provide for increasing or decreasing rent (beyond the safe harbors available in Section 467) or material amounts of prepaid or deferred rent. When lease agreements are restructured as a result of a default by the tenant in a bad or uncertain economy, however, and the parties decide to be creative in restructuring the lease, the possibility of falling into the Section 467 rabbit hole becomes very real.

Our lawyers have been involved in dealing with the tax issues in lease agreements and the intricacies of Section 467 lease agreements since the enactment of Section 467 in 1986. We can help you to restructure the lease agreement to side-step Section 467 in many instances or, in some cases to make the agreement a section 467 lease agreement in order to take advantage of the particular rules applicable to those arrangements.