As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to sweep through the United States, state attorneys general (AGs) are updating their playbooks in an effort to deal with this unprecedented crisis. They are wielding their legal, political, and policy-making authority and increasing enforcement to protect consumers, enhance data privacy and security, eliminate price-gouging, and combat false claims for payment to state authorities. In this article we look at how addressing the crisis has expanded AGs’ areas of focus and consider the implications for businesses.

Guardianship of Consumer Rights Will Continue

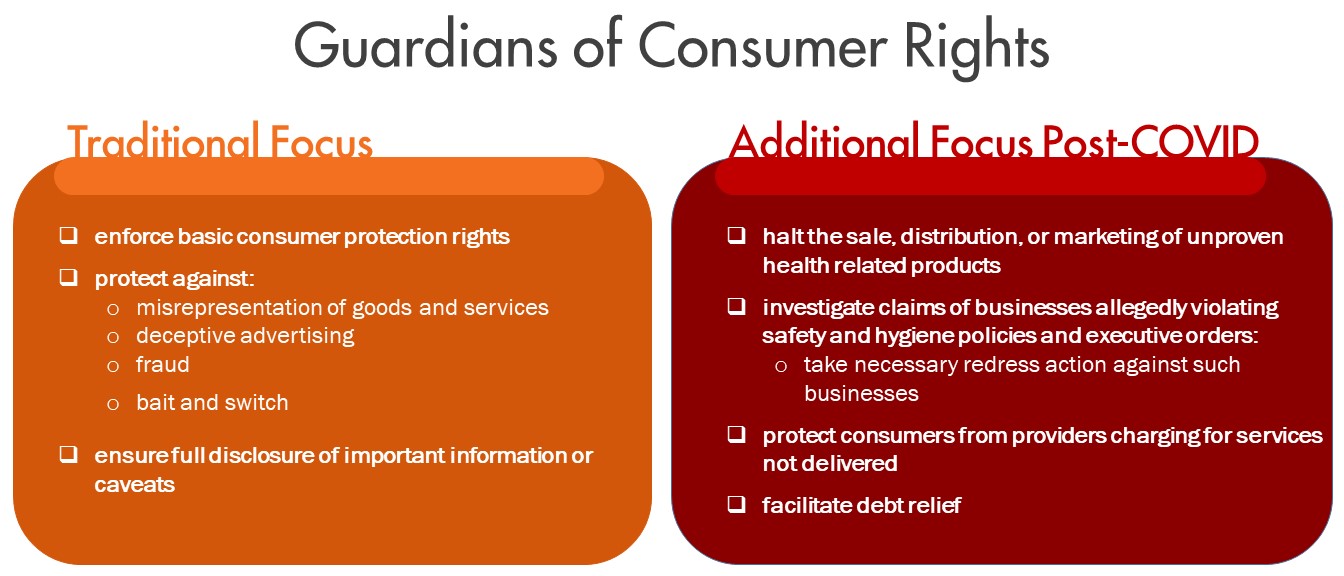

AGs’ sweeping consumer protection authority was well established prior to the COVID-19 crisis and is underscored by the AGs’ swift actions in response to the pandemic.

-

Within days of hucksters and charlatans starting to peddle fake treatments and cures for the virus, AGs, including New York AG Leticia James and Missouri AG Eric Schmitt, had issued cease-and-desist letters or sued under their broad state unfair and deceptive acts and practices (UDAP) laws to bring such misconduct to a halt.

-

AGs across the country developed dedicated webpages, activated hotlines, issued frequent consumer alerts, and encouraged the public to report COVID-related scams and fraud, which ranged from fake treatments to impersonation of health care workers to stimulus check scams.

-

AGs broadened their focus on misleading advertising and marketing to include statements related to COVID-19. For example, Florida AG Ashley Moody began an investigation into cruise package marketing and disclosures related to the pandemic.

AGs’ consumer protection actions in response to the health crisis have included new tactics to supplement the traditional approaches of investigations and lawsuits. Some AGs applied pressure on businesses like sports clubs, television providers, and others to suspend or reduce fees and eliminate penalties, and many AGs themselves have temporarily suspended the collection by their offices of certain debt owed to the state. A number of AGs empowered with rulemaking authority have promulgated temporary or emergency rules, such as Oregon AG Ellen Rosenblum’s temporary rule mandating “adequate substantiation” for alleged COVID-19 treatments, and Massachusetts AG Maura Healey’s emergency regulation — challenged in court — significantly curtailing private debt-collection activities in the state, including filing new lawsuits, repossessing cars, and making unsolicited debt collection calls.

As life with COVID-19 becomes the status quo, AGs will undoubtedly continue to exercise their consumer protection authority to deter scammers. It is also foreseeable that well-meaning companies will come under scrutiny due to difficult choices they faced during the government-mandated shutdown — and the subsequent economic downturn — resulting in consumers not receiving the full benefits of paid-for goods or services, or being negatively impacted in other ways. Sectors that are likely to receive particular attention include:

-

Assisted-living facilities and nursing homes that experienced high infection rates. Massachusetts AG Healey and New Mexico AG Hector Balderas, among others, have begun investigating, establishing a roadmap for potential litigation.

-

Other businesses or organizations that could have served as vectors, like hotels, restaurants, gyms, and conference organizers. Not only will these businesses need to be accountable for what they said and did prior to the shutdown, but they will now need to be concerned with any public claims they make about the procedures in place to safeguard consumers’ health and safety.

-

Businesses that disregarded executive orders and other regulations regarding the shut-down or reopening. AGs will allege that such behavior represents unfair, misleading, and deceptive conduct.

Time is on the AGs’ side, as the statute of limitations on an AG lawsuit may range from two to up to six years depending on the state — with AGs in some states not subject to a limitations period at all.

Evolving Technologies Create New Challenges

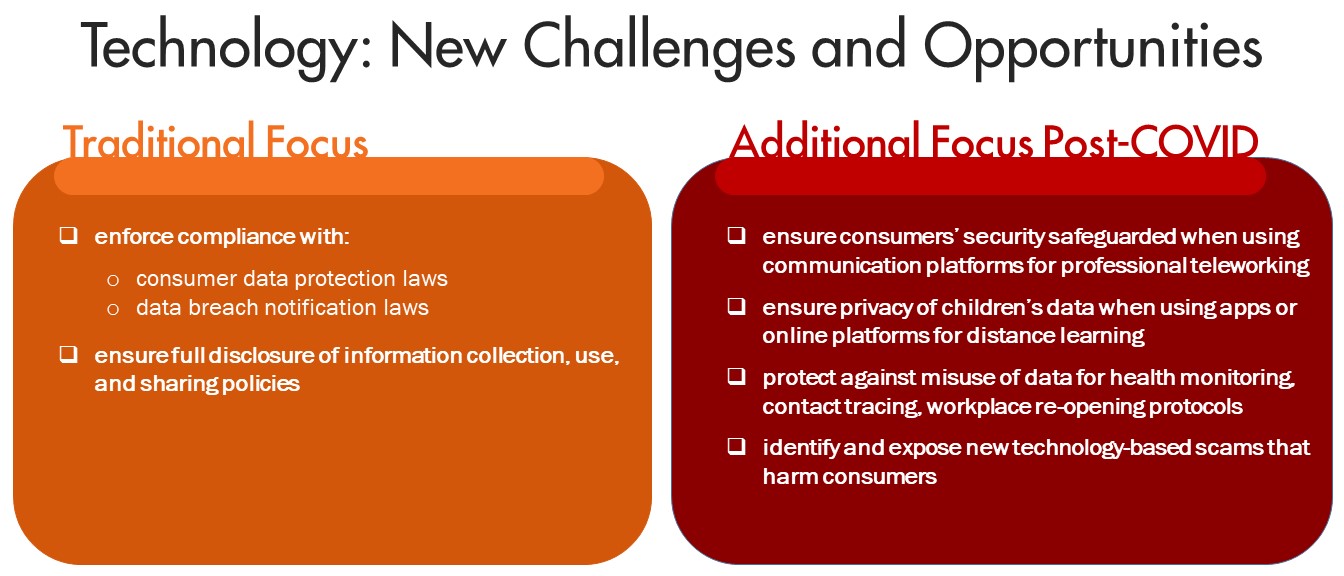

Data privacy and security is far from a new focus area for AGs — indeed, they are the de facto national regulators in this area in the absence of federal regulation. AGs have long been leaders in policing the ways companies collect, transfer, and use consumer data and what they tell consumers about those practices. The COVID-19 pandemic has, however, raised new concerns around what data is collected and shared, and presents new opportunities for data thieves.

-

In the earliest days of the pandemic, AGs such as Maryland’s Brian Frosh and Virginia’s Mark Herring warned consumers of phishing emails from scammers trying to steal personal information by posing as personnel from health organizations.

-

In an effort to reduce deceptive advertising, phishing schemes, and malware dissemination through coronavirus-related domains, New York AG James requested that domain name registrars apprise her of the steps they were taking to protect consumers.

-

As stimulus checks started to roll out, cyber criminals initiated yet other scams, including claiming to be representatives of the Internal Revenue Service or U.S. Treasury Department.

-

A number of AGs, including New York AG James, Florida AG Moody, and Connecticut AG William Tong, announced investigations into video-conferencing platform Zoom, which experienced a massive surge in demand as offices closed down and workers went online. Their attention to the accuracy of Zoom’s consumer disclosures and other security measures resulted in the company announcing new practices and security protocols.

Technology is certain to be at the top of AGs’ minds as government-imposed lockdowns begin to be lifted. As consumers and businesses have become far more dependent on teleworking and receiving educational and other services remotely, they are increasingly at risk of phishing and privacy attacks by hackers capitalizing on vulnerabilities resulting from the explosion in demand.

In addition, success in containing new COVID-19 outbreaks will depend on applications and tools that facilitate data collection to monitor social distancing. More invasive tools are also in development that conduct digital contact tracing by tracking the devices an individual smartphone has been near — generating more data that risks exposure, misuse, or theft. The response to the virus has and will continue to involve novel, untested collection, use, and transfer of data on a previously inconceivable scale, and AGs can be expected to police these cutting-edge technologies vigorously.

Price-Gouging Is a Concern Up and Down the Supply Chain

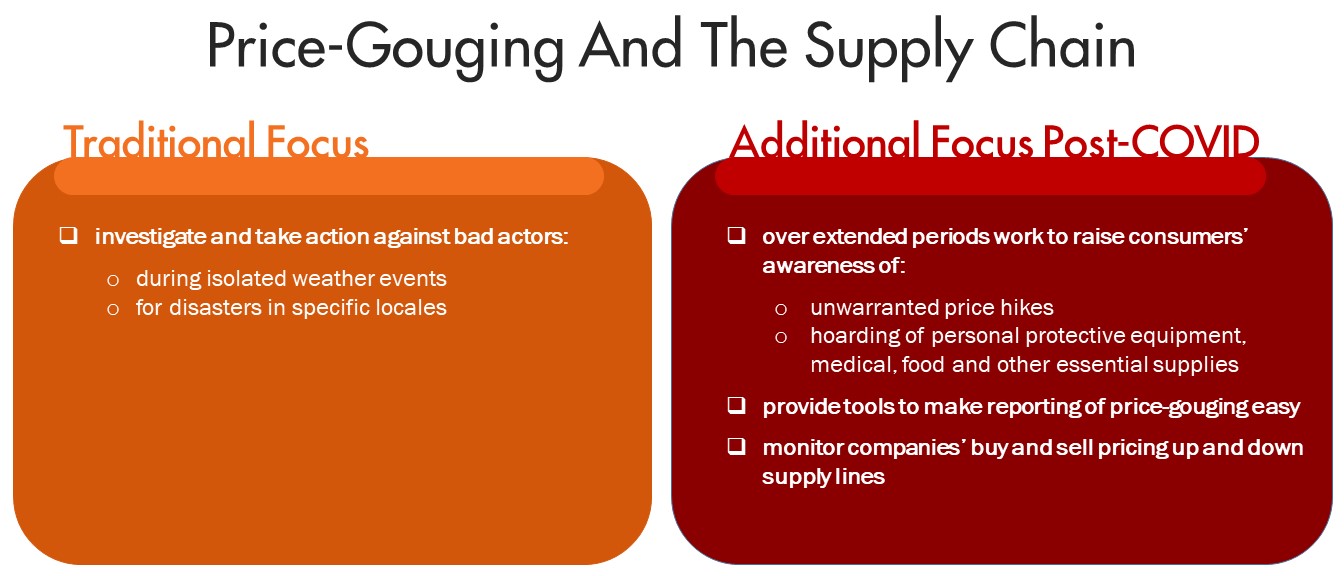

Price-gouging laws have traditionally been invoked only in cases of short-term crisis, like hurricanes, floods, or other natural disasters. It remains an open question how AGs will apply these laws in a state of emergency that will likely persist for many months, exposing companies at all levels of the supply chain as they struggle to cope with economic distress and global supply disruptions.

Before the current pandemic, declarations of emergency also typically did not involve the entire country at once. The national scale and unusually long duration of the current pandemic, however, is giving rise to novel issues and concerns as AGs have increasingly sought to enforce price-gouging laws.

-

Some AGs, like Arkansas AG Leslie Rutledge and Florida AG Moody, have publicly commended online retailers for steps they have taken to prevent price gouging.

-

But AGs may come to call for further action, like the bipartisan group of 33 AGs who wrote to major retailers urging them to implement additional solutions and safeguards to protect consumers.

The current climate of uncertainty makes it more critical than ever for companies to implement practices to protect them from price-gouging allegations. Many laws, such as those of California and Florida, contain exceptions if the seller can prove the price increase was the result of additional costs up the supply chain. Companies should document input price increases and internal justifications for increases thoroughly.

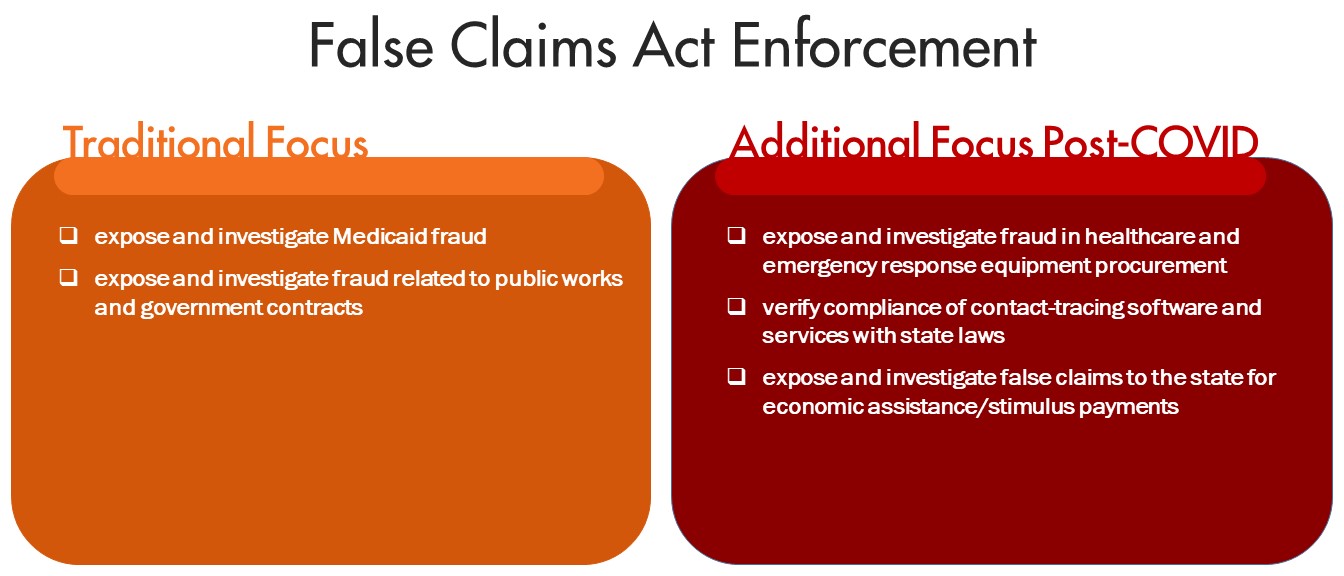

AGs Will Actively Pursue False Claims

State False Claims Act (FCA) enforcement potentially offers even more opportunities for increased AG involvement. Most states allow AGs to sue individuals and entities alleged to have submitted false claims for payment to the state, and the FCAs of 30 states and DC also permit private plaintiffs to file such lawsuits in the name of the state through so-called qui tam actions. In the wake of the 2008 mortgage crisis FCA actions saw a significant uptick as governments committed billions of dollars to assist borrowers facing foreclosures. A similar uptick is even more likely following the COVID‑19 pandemic, given the state and local focus.

States, cities, and counties have contracted for billions of dollars in health care and emergency response equipment, with more likely to be needed as their economies reopen and the demand for testing and monitoring skyrockets. Examples like New York state’s alleged payment of more than $69 million for ventilators at the peak of the crisis likely represent the mere tip of the FCA iceberg. With qui tam plaintiffs empowered to act on behalf of the state on their own, AGs will need to decide whether to intervene and pursue the case or let the private party continue. California’s AG has already sponsored legislation that is moving in the assembly to expand the scope of that state’s False Claims Act.

Companies contracting to provide government services or products should review their quality-control, invoicing, and record-keeping policies, and ensure they are in full compliance with any eligibility requirements imposed by government contracts, including qualifications for small business or minority/woman/veteran-owned status.

Increased Political and Financial Pressure for AGs to Act

AG offices are feeling the same budgetary pressures as the private sector as the result of the economic crisis, as evidenced by Michigan AG Dana Nessel’s decision to temporarily lay off 25 percent of her staff in late April. Therefore, in addition to their motivation to protect the citizens of their states, AGs will be under political and financial pressure to find new targets for investigations and litigation because many AG consumer protection offices are at least in part self-funded from the proceeds of settlements, litigation recoveries, and enforcement penalties. As state legislatures look to tighten belts, AGs will likely be compelled to find alternative sources of funding, just as they did in the wake of the 2008 mortgage crisis and subsequent recession. Litigation driven by AGs in that time resulted in some of the largest settlements in history, including the $25 billion mortgage servicing settlement and $1.37 billion Standard & Poor’s credit ratings settlement. The post-2008 activism by AGs is likely to repeat itself in 2020 and beyond.

Smart Businesses Will Engage with AGs Early and Often

AGs’ expansive array of legal and policy tools, and broad enforcement authority and discretion, have propelled them into a leading role in responding to the COVID-19 crisis. Yet perhaps what has become most clear about AGs during this time when everything is changing is what has remained the same. As they have done before, AGs will continue to quickly and effectively respond to new crises, and to shape state laws and how they are enforced. This presents new opportunities for businesses that proactively and positively engage with AGs — and challenges for those that fail to do so.